How To Accept Yourself: A Guide To Self Acceptance

Feb 06, 2022We all want to feel good about ourselves. Understandably so.

The need to maintain and enhance self-esteem is widely assumed to be a fundamental human motive [1]. It is a basic human desire to feel the need to belong [2]. From an evolutionary perspective, belonging to social groups carries several advantages in terms of survival, reproductive opportunities and success [3].

We try to prove our worth, so that we belong, so that we survive. Makes sense.

So how do we do that?

In Western culture, having high self-esteem means standing out in a crowd—being special and above average [4]. We feel successful when we look good, earn lots of money and are accepted by others. We value ourselves based on our characteristics, behaviours, achievements and outside approval.

But there’s a problem.

This incessant need to feel worthy can motivate us to work hard and succeed, but it also makes us emotionally vulnerable to setbacks. People whose self-esteem is more contingent on meeting high standards of achievement and competence report greater maladaptive perfectionism [5]. Women whose self-esteem is more contingent on standards of attractiveness will experience greater body dissatisfaction [6]. In trying to feel better, we often feel worse.

When our self esteem is conditional, we become preoccupied with achievements and social acceptance [7]. Yet chasing accomplishments or approval from others to feel good about ourselves is a temporary solution at best, since it depends on things going well. Even if we are doing well, we may be anxious to lose what we’ve gained. Each and every one of us will make a mistake at some point or another, no matter how hard we try. If you convince yourself you need to be perfect, then failure is going to hit you pretty hard when it arrives.

Contrary to what the popular self help books might suggest, boosting our self-esteem may not be the most effective way to protect our self-worth.

[8]

The pursuit of self-esteem perpetuates the underlying problem: an irrational philosophy of self-rating. We try to establish our worth as people through the things that we do. Achieving more makes us better people. Failing makes us worse. We have a hard time separating judgments of our accomplishments from judgements of ourselves.

But how can we ever accurately rate ourselves as people?

There are a few reasons as to why it’s an impossible task:

- You are way too complex to ever accurately rate yourself as a person.

- Who you are is constantly changing; you are a work in progress

- Given similar circumstances, people are basically alike (no time to go into this here but I recommend reading Behave by Sapolsky)

‘You’ cannot be reduced to the things you do or achieve

I mean, who are you anyway? There are many ways you could answer this question.

When introducing yourself to someone new, you might start by describing where you’re from and what you do for a living. Perhaps you’ll list off some of your hobbies and interests. You could think of yourself in terms of your relationships: a husband/wife, a son/daughter, a brother/sister, or a friend. Your personality traits are also a part of who you are. Perhaps you’re funny, adventurous, compassionate or outgoing. And maybe there are times you feel the complete opposite is true about you!

You’ll likely still feel like this description doesn’t capture the whole ‘you’. The point is you have multiple identities and character traits, and these change over time. Not only will rating yourself as a person likely make you anxious and miserable, but it’s also impossible to do.

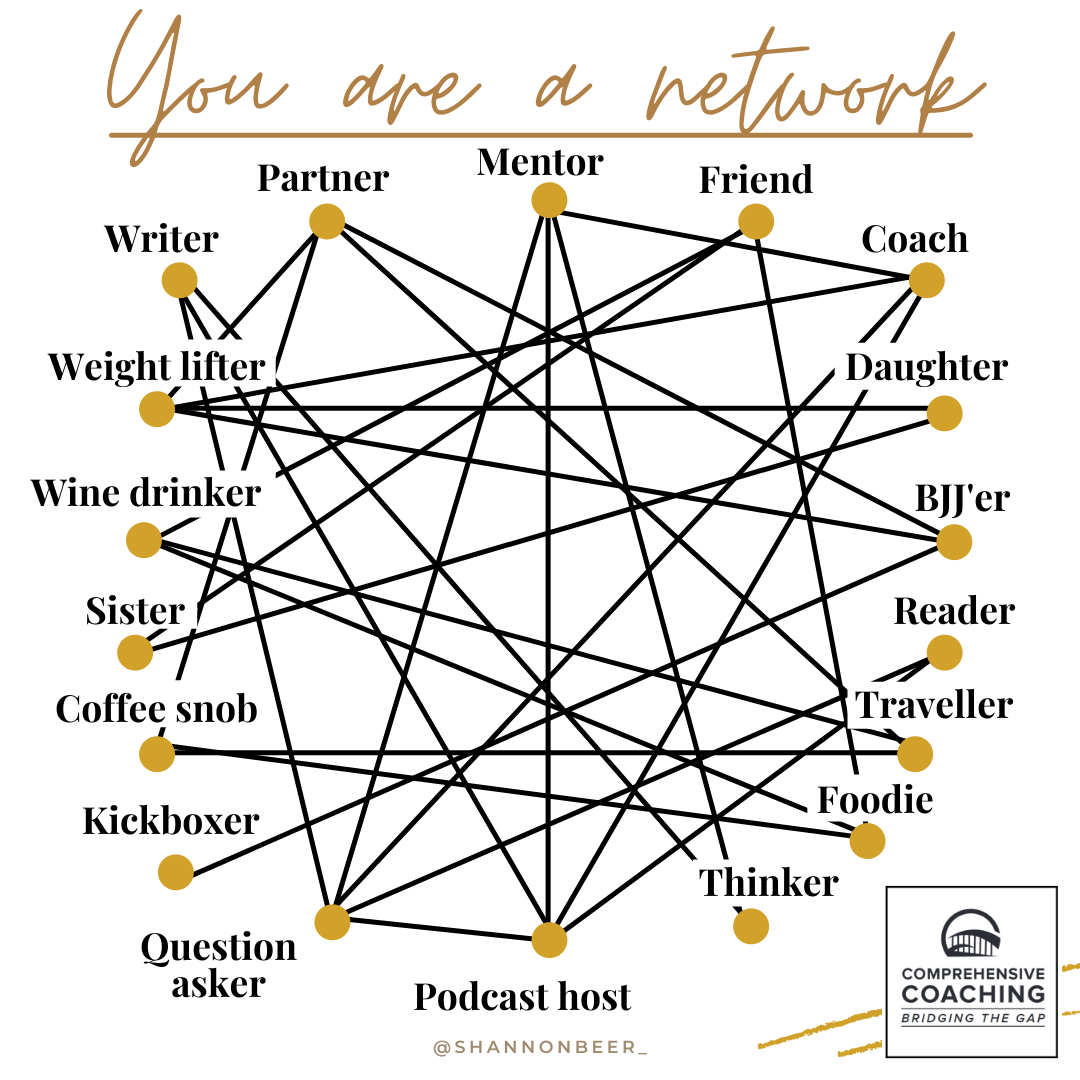

You can think of yourself in terms of a network:

How do you define yourself as a person? What hobbies do you engage in? What relationships are important to you? What character traits do you possess? What do you care about?

When you’re feeling crap for not performing well at something, remember that it’s not the only thing you do.

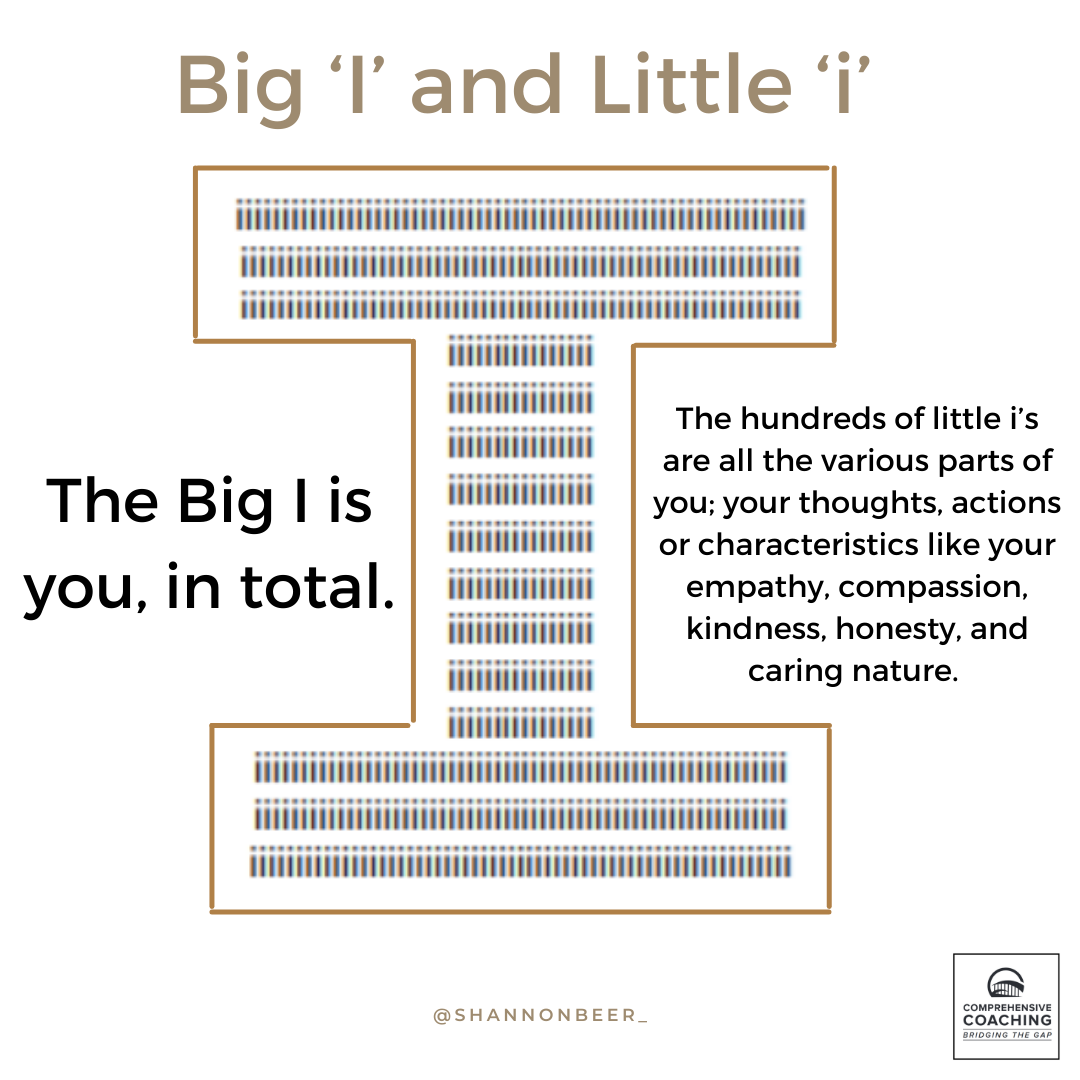

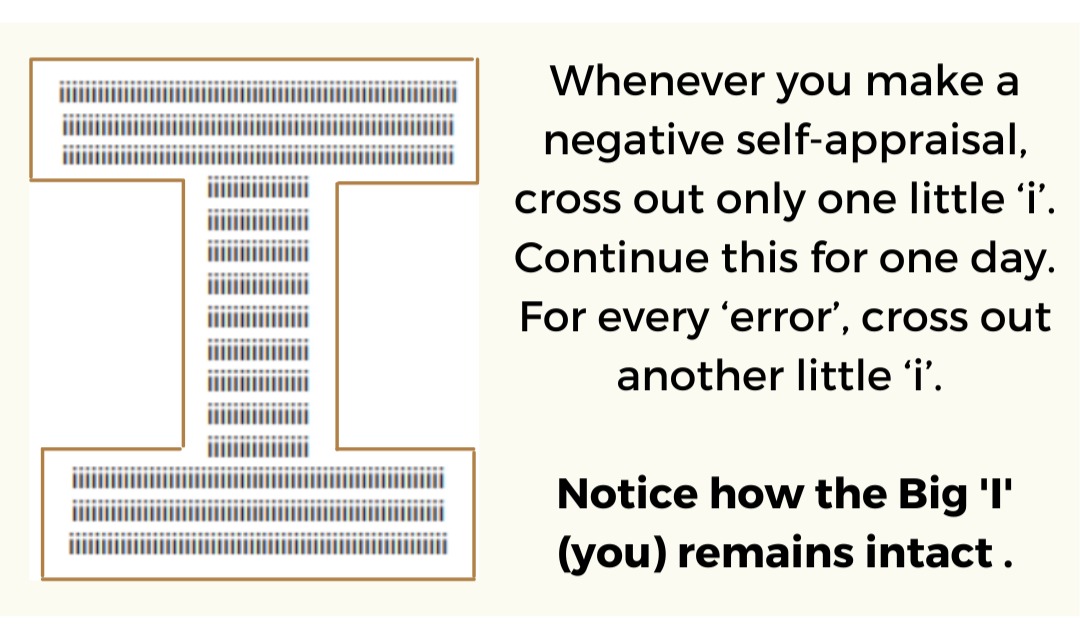

Rather than there being one “I” or self, it has been suggested that the self is composed of many “I”s [9]. There is the ‘I’ that spends time with friends, the ‘I’ that pursues sports performance goals, the ‘I’ that runs a business, and the ‘I’ that cares for one’s partner, and so on. The whole self is then not put down if one ‘I’ is faulty.

If you tend to feel like a total failure every time you make a mistake, give this exercise a go:

Recognise that one small mistake doesn't reflect your total character. You can evaluate your actions, including mistakes or weaknesses, without condemning yourself as a person.

Whilst the need to belong is a natural human desire, our incessant need for positive self-regard isn’t universal. Our experience of the ‘self’, who we are and how we feel about ourselves, has been heavily influenced by what our culture deems to be important. For example, individuals from Eastern Asian cultures affirm themselves not as autonomous agents who need to succeed, but through the relationships that they are a part of [10].

We can resist the pressure to be perfect by thinking for ourselves and developing acceptance from within. We can construct our own meaning and identity by challenging our self-views. We can feel worthy as individuals, not by achieving a positive self-regard, but by maintaining a realistic view. Feeling good about ourselves is important; viewing ourselves overly positively is not.

The Road To Self Acceptance

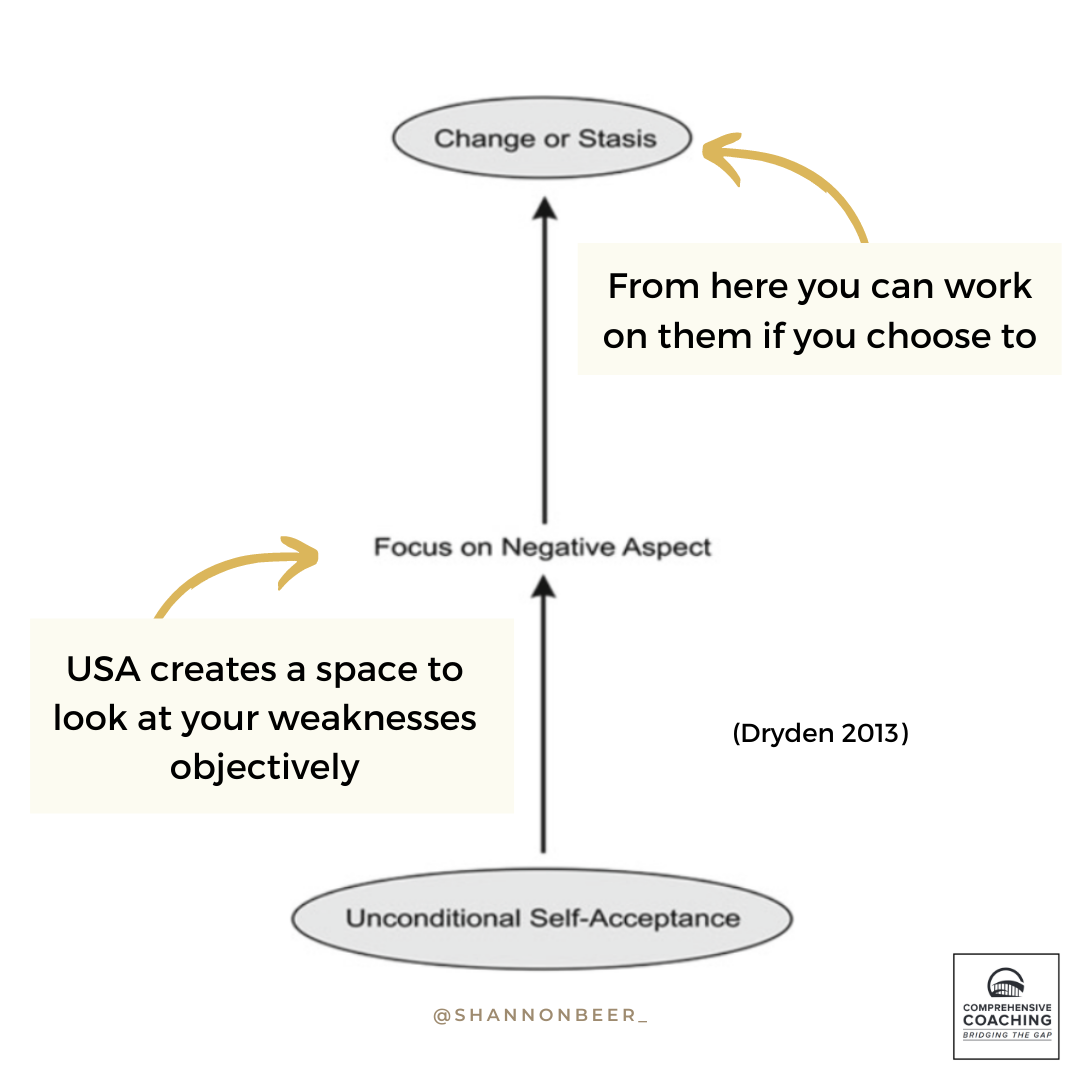

Accepting yourself for who you are does not mean you must like, appreciate, or celebrate every aspect of yourself. Unconditional self-acceptance means that ‘the individual fully and unconditionally accepts himself whether or not he behaves intelligently, correctly, or competently and whether or not other people approve, respect, or love him’ [11]. It’s about developing realistic self views by acknowledging both strengths and weaknesses, rather than focusing on one at the expense of the other.

We all have weaknesses. We all make mistakes. We all fail from time to time.

Having something to improve on is not a fault. It makes you human.

You probably scoffed at the idea of accepting yourself. Sounds a bit too soft. I get it.

There’s a tendency to believe that unconditionally accepting oneself equates to stagnation, or giving up. That if we learn self acceptance, we’ll end up resigning ourselves to the things we dislike.

This is not the case.

On the contrary, when we learn to accept ourselves, we’re actually in a better position to work on our weaknesses, because we’re not trying to hide them.

Self-acceptance may be viewed as the first step towards working on our weaknesses in a healthy manner. Acknowledging and accepting ourselves unconditionally allows us to strive for our goals without self-hatred, shame, or anxiety. We can put ourselves out there, set the bar high, and take risks, because our entire self-worth isn’t shattered when we don’t make it. People who accept themselves unconditionally are more resistant to ego-provoking situations such as failure or rejection [12]. By removing the conditions upon which we judge ourselves, we give ourselves the space to change and grow.

Unconditional self-acceptance allows you to rate your actions and traits, and encourages such ratings as a means of personal change and improvement [13]. The difference is that you refrain from rating yourself. From this perspective, you can face your faults without beating yourself up so much. Liberated from feelings of inadequacy, and fear of criticism and rejection, you are free to explore and pursue the things that really make you happy.

Building Self Acceptance

The following exercise will provide a practical place to start:

Write a list of things you do well and the positive character traits you possess:

Now write down what you consider to be some of your weaknesses:

Ask yourself:

Is it reasonable to conclude that you're a total failure, or a terrible person, because you have weaknesses, just like the rest of us?

We tend to try to see our successes as good, and the failures as bad, but what if we see that everything is something to learn from?

What do you appreciate most about your personality? What aspects do you find harder to accept?

Summary

‘Minus such a self-rating, and minus playing the ego game and the power struggle of vying for ‘goodness’ with other human beings, you can ask yourself ‘What do I really want in life?’ and can try to find those things and enjoy them.’ - Albert Ellis

- We all want to feel worthy, but enhancing self esteem by chasing achievements or approval leaves us emotionally vulnerable to setbacks.

- Realise that you are fallible, just like the rest of us. Check the demands you are placing on yourself.

- Accept yourself unconditionally as a unique, complex individual who is in flux and cannot be validly given a global evaluation.

- Notice your self talk when you are judging yourself; consider reframing it using the strategies outlined in THIS article.

- Learn from your mistakes rather than punishing yourself for them.

Self-acceptance can only come from you, and you are free to choose it at any time.

References

[1] Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518

[2] Baumeister, Roy & Leary, Mark. (1995). The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychological bulletin. 117. 497-529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

[3] Brewer, M. B. (2004) Taking the social origins of human nature seriously: Toward a more imperialist social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(2), 107-113. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0802_3

[4] Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106(4), 766–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766

[5] Szpitalak, M., Polczyk, R., & Dudek, I. (2018). Psychometric properties and correlates of the Polish version of the Contingent Self-Esteem Scale (CSES). Polish Psychological Bulletin, 449–457-449–457.

[6] Szpitalak, M., Polczyk, R., & Dudek, I. (2018). Psychometric properties and correlates of the Polish version of the Contingent Self-Esteem Scale (CSES). Polish Psychological Bulletin, 449–457-449–457.

[7] Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy: The basis for true self-esteem. In M. H. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31–49). Plenum Press.

[8] Crocker, J., & Knight, K. M. (2005). Contingencies of Self-Worth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 200–203. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20183024

[9] Franklin, R. (1993). Overcoming the myth of self-worth. Appleton, WI: Focus Press.

[10] Heine, Steven. (2002). Self as Cultural Product: An Examination of East Asian and North American Selves. Journal of personality. 69. 881-906. 10.1111/1467-6494.696168.

[11] Ellis, A. (1977). Psychotherapy and the value of a human being. In A. Ellis & R. Grieger (Eds.), Handbook of rational-emotive therapy (pp. 99–112). New York, NY: Springer.

[12] Davies, M. F. (2006). Irrational beliefs and unconditional self-acceptance. I. Correlational evidence linking two key features of REBT. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 24, 113–124.

[13] Bernard, M. (2011). Rationality and the pursuit of happiness. The legacy of Albert Ellis. Chichester:Wiley-Blackwell.

Trying To Grow Your Coaching Business?

Join the Beneath The Surface newsletter to receive weekly tips to grow a meaningful coaching business, make more money and build your dream life.

If it's shit, you can always unsubcribe.