What Does It Mean To Be Healthy?

Jan 24, 2022

‘We are being led to the conclusion that we each must make our own definition of health, just as we each define ‘the good life’’ - Sigmund Freud

The way we define health determines the way we strive towards it; so, it is essential to have a clear idea of what we are actually aiming for. When taking steps to improve our health, we typically focus on very narrow outcomes such as how we perform in the gym, or even how we look in the mirror. Although these metrics have their place, they offer an incomplete picture of health, which can be conceived of as a dynamic state of whole person adaptation to an ever changing and demanding environment. Reducing the complexity of health down to a few simple and easy to measure variables, like macros and bodyweight, is epistemically flawed. If we truly want to live healthier lives and help others to do the same, we must take a more expansive perspective on health and wellbeing.

But First... Why Should We Care?

Our state of health has a huge impact on our quality of life, physical function, mental health, cognition and social interactions. A positive state of wellbeing is associated with numerous benefits related to health, work, family, and economics [1]. It pays to have an understanding of it.

How Should We Define Health?

Defining health is pretty tricky, due to its intangible, complex, adaptive and emergent nature. We can’t see health like we can see our bodies in the mirror, and we can’t measure it like we can with our weight on the scales. Even more crucially, we cannot visibly see all of the factors that influence it either - it is not as simple as having the ‘right’ foods on our plates, no matter how perfectly structured the macronutrients may be.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ [2]. The recognition of mental health was revolutionary at the time, facilitating a paradigm shift away from the Cartesian-based mind-body dualism that had been dominating the biomedical field. Although many consider this definition to be conventional wisdom [3], it raises some important questions. What do we mean by complete? Rather than defining health as a negative state, ‘the absence of’, we should consider the positive, personal dimensions of health that we can actively seek out in our daily lives.

VanderWeele imagines health in terms of ‘flourishing’, meaning to grow and prosper across different domains of life [5]. Flourishing is a multi-dimensional construct comprised of six domains:

-

Happiness and life satisfaction

-

Physical and mental health

-

Meaning and purpose

-

Character and virtue

-

Close social relations

-

Financial and material stability, as a means of securing the other five domains of flourishing

When we take care of our physical and mental health, foster deep social relationships, feel connected to a sense of meaning and purpose, live virtuously and feel satisfied with our lives, we flourish. Aristotle declared flourishing as the ultimate goal of human existence; he viewed it as being important in its own right, not just as a means to an end [6]. Could he have been on to something?

Flourishing health incorporates aspects of wellbeing, which is understood not simply as positive emotions, but, rather, as thriving across multiple domains of life [7]. In the eudaemonic paradigm, wellbeing is construed as an ongoing, dynamic process (rather than a fixed state) of effortful living by means of engagement in meaningful activities [8]. We can conceive of our pursuit of health as a similarly dynamic process; we are constantly in a state of flux, constructing and adapting to our environments. Our state of health is not static but rather a dynamic emergent whole person phenomena [9].

Causal Pathways

Although conceptually distinct, the domains of flourishing health are far from independent. Our physical health can affect our mental health, and vice versa [10]. Our social relations can have positive or negative effects on our health, both physically and mentally [11]. Financial insecurity is related to poor physical and psychological health outcomes [12] and is an independent predictor for both the onset and persistence of episodes of mental disorders [13]. A life lived in pursuit of virtue is likely to lead to a sense of meaning and purpose. These facets of health do not operate in parallel; they are intertwined and cumulative.

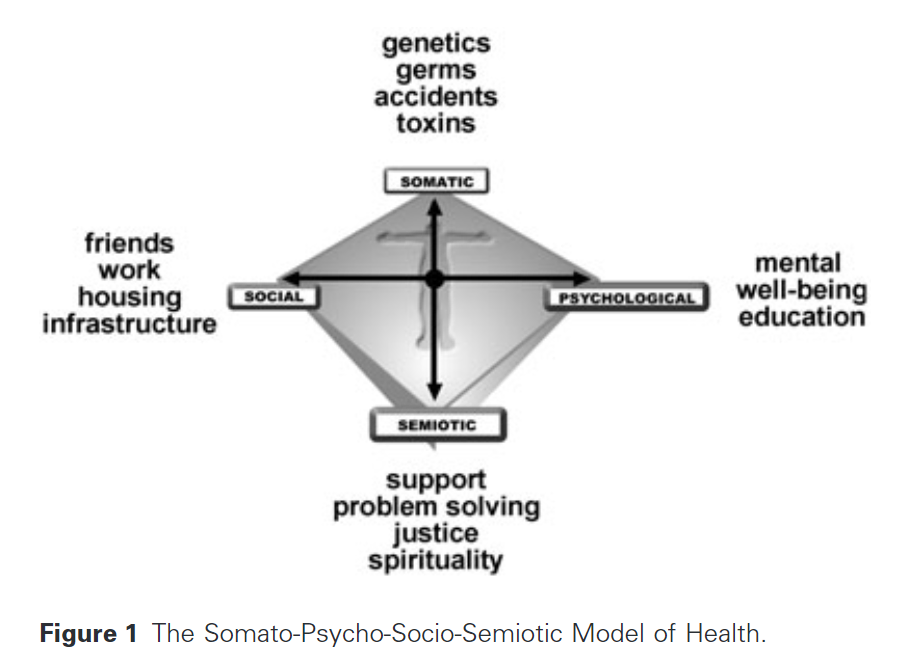

The somato-psycho-socio-semiotic model of health provides us with a framework to make sense of how these domains of health interact [14]. This model describes health as a balance resulting from dynamic interactions between the biological, emotional, social and cognitive dimensions affecting an individual.

Social Health

'Social man...is the masterpiece of existence'- Émile Durkheim

Whether we like it or not, we are each members of a collective enmeshed in relations of different social networks. These networks can have a huge influence on our health [15]. In Suicide, sociologist Emile Durkheim put forward the groundbreaking argument that rather than simply being a result of individual temperament, suicide can have origins in social causes. He concluded that the more socially integrated and connected a person is, the less likely he or she is to commit suicide [16]. At the time, this was a radical insight into the relationship between society and health.

Over a hundred years later, scientific research indicates that a lack of social connectedness can have a huge impact on our health through cognitive, affective and behavioural pathways. Data across 308,849 individuals, followed for an average of seven and a half years, indicate that individuals with adequate social relationships have a 50% increased likelihood of survival than those who did not [17]. Lonely individuals see the world as a more threatening place and isolation increases activation of the HPA axis leading to neural, neuroendocrine and behavioural responses that promote short-term self-preservation [18]. It is increasingly evident that maintaining meaningful social relations is protective of our health through a number of potential pathways [19].

In our pursuit of health, we often neglect our psychological well being. Perhaps this is because it’s not something we can easily see or measure - it’s certainly not captured in our ‘before and after’ progress photos. Mental health is defined as ‘a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his own community’ [20]. Good mental health contributes significantly to our quality of life and is associated with better physical health outcomes, improved educational attainment, increased economic participation, and rich social relationships [21].

Our psychology and physiology are intertwined; our brain is the central organ that responds to stress and it communicates reciprocally with the rest of the body. While short-term stressors promote adaptation in a constantly changing environment, persistent, and/or high levels of stressors contribute to enduring physiological dysregulation via neuroendocrine, autonomic, immune, minimises allostatic load [22]. Our mental health exists along a spectrum and we will all face challenges throughout our lives that will influence our needs. Resilience, the ability to adapt in the face of adversity, mitigates the maladaptive stress response and enhances psychological health. Optimism, cognitive reappraisal, self-regulation, adaptive coping strategies, social support, humour, mindfulness, physical exercise and prosocial behaviour have all be associated with increased resilience [23].

While the determining factors of mental health are complex, it is evident that physical exercise and nutrition are not only critical for our physiology and body composition, but also have significant effects on mood and mental wellbeing [25], [26]. Although these behaviours can have great benefits, they also have the potential to cause significant harm [27], [28]. We inhabit our bodies but we live in our minds; the great paradox is that we often prioritise the former at the expense of the latter. It is stated that the minds and brains can be both servants and masters of the bodies and, surely, it is mastery we are aiming for...

‘He who has a why to live can bear almost any how’ - Friedrich Nietzsche

Life is full of challenges and stressors to which we must constantly adjust and adapt. Antonovsky proposes a systems theory information-processing model to grasp the realities of the inevitable conflicts accompanying us throughout our lives, submitting that ‘how one copes with such conflicts...is a decisive factor in shaping health’ [29]. Viktor Frankl, Austrian psychiatrist and founder of logotherapy, a meaning-centred school of psychotherapy, attributed his psychological endurance and survival of concentration camps to a robust sense of meaning and purpose. ‘In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning’, he states [30].

Sense Of Coherence (SOC) is defined as an individual's propensity to view the world as comprehensible, manageable and meaningful [31]. Research suggests that levels of perceived control over life are an important predictor of dietary quality in women with low educational attainment [32], supporting the role of SOC in one’s health. Purpose in life is posited to play an important role in building resilience, coping against adverse life events, and psychological well-being [33]. Grit has been associated with improved psychological well-being and satisfaction with life; an association made stronger when SOC is present [34]. It seems that our ability to create meaning and make sense of things is an important determinant of our health.

Wrapping It All Up...

'The meaning of health is complex and subject to change' - James S Larson

This article argued that great health is an individual state of flourishing that expands far beyond the physical domain to all aspects of our lives. I used the somato-psycho-socio-semiotic model of health to illustrate how different causal pathways interact to create an emergent, dynamic state of wellbeing, unique to each individual. My purpose was not to provide a definitive answer to the question of what health is, but to promote a broader conceptualisation of factors related to health improvement as a consideration for daily living.

Many of our decisions about how to live day to day relate not just to health or happiness, but also more broadly to relationships, meaning, and purpose. We may intend to diet to reach a weight loss goal, for example, but face conflicting desires about wanting to eat out and socialise with friends. Focusing exclusively on our physical health may conflict with other important individual values and have downstream effects on other aspects of our wellbeing. Looking solely at numbers and measurements as markers of health misses the bigger picture and obscures other signs of healthy progress.

To promote flourishing health is to empower individuals to identify their internal and external resources, to use them to realise aspirations, satisfy needs, foster secure relationships, and cope with the environment in an adaptive manner, so that they can live meaningful and purposeful lives. This is the principal aim of Comprehensive Coaching.

I will leave you with this quote, which I have unfortunately lost the reference for. If anyone knows where I found it, please give me a shout.

‘Health is a more fundamental concept, the meaning of which must be presupposed by empirical disciplines to determine the mechanisms and causal pathways by which it is lost and gained—but a meaning that cannot be discovered by any such empirical means. Determining the nature of health is a more fundamental project, which, in a sense, precedes the empirical study of the processes and mechanisms that influence it’.

References

[1] Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull 2005; 131(6):803–855.

[2] Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution

[3] Greenfield, S., & Nelson, E. (1992). Recent Developments and Future Issues in the Use of Health Status Assessment Measures in Clinical Settings. Medical Care,30(5), MS23-MS41. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3766227

[4] Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, 1844-1900. The Gay Science; with a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs. New York :Vintage Books, 1974.

[5] VanderWeele TJ, McNeely E, Koh HK. Reimagining Health—Flourishing. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1667–1668. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3035

[6] Collins. (2011). Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. University of Chicago Press

[7] DIENER, Ed, SCOLLON, Christie N., & Lucas, Richard E.. (2003). The Evolving Concept of Subjective Well-Being: The Multifaceted Nature of Happiness. In Recent Advances in Psychology and Aging (pp. 187-219). Amsterdam: Elsevier

[8] Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

[9] Sturmberg JP, Picard M, Aron DC, et al. Health and Disease-Emergent States Resulting From Adaptive Social and Biological Network Interactions. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:59. Published 2019 Mar 28. doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00059

[10] Ohrnberger J, Fichera E, Sutton M. The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;195:42-49. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.008

[11] Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017;152:157-171. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

[12] Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social Determinants of Health. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006.

[13] Weich S, Lewis G. Poverty, unemployment, and common mental disorders: population based cohort study. BMJ. 1998;317(7151):115-119. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7151.115

[14] Sturmberg JP. The personal nature of health. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):766-769. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01225.x

[15] Cohen, Sheldon. (2004). Social Relationships and Health. The American psychologist. 59. 676-84. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676.

[16] Durkheim, Émile. "Suicide: A Study in Sociology." Trans. Spaulding, John A. New York: The Free Press, 1979 (1897).

[17] Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. Published 2010 Jul 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

[18] Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29(4):377-387. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

[19] Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843-857. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4

[20] World Health Organization (2007). What is mental health? Retrieved on September 14, 2020 from http://www.who.int/features/qa/62/en/index.htm

[21] Friedli, L., & Parsonage, M. (2007). Mental health promotion: Building an economic case. Northern Ireland Association for Mental Health

[22] McEwen BS.Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Thousand Oaks, CA:Chronic stress (2017).

[23] Wu G, Feder A, Cohen H, et al. Understanding resilience. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:10. Published 2013 Feb 15. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00010

[24] Retrieved on September 14, 2020 from https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/

[25] Singh, N.A. et al. (2005) A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.60, 768–776

[26] Marx W, Moseley G, Berk M, Jacka F. Nutritional psychiatry: the present state of the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76(4):427-436. doi:10.1017/S0029665117002026

[27] Schaumberg K, Anderson DA, Anderson LM, Reilly EE, Gorrell S. Dietary restraint: what's the harm? A review of the relationship between dietary restraint, weight trajectory and the development of eating pathology. Clin Obes. 2016;6(2):89–100. https://doi:10.1111/cob.12134

[29] Antonovsky A.Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 1979

[30] Frankl V. E. (2006). Man's Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press

[31] Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725-733. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z

[32] Barker M, Lawrence W, Crozier S, et al. Educational attainment, perceived control and the quality of women's diets. Appetite. 2009;52(3):631-636. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2009.02.011

[33] Andree Hartanto, Jose C. Yong, Sean T. H. Lee, Wee Qin Ng & Eddie M. W. Tong (2020) Putting adversity in perspective: purpose in life moderates the link between childhood emotional abuse and neglect and adulthood depressive symptoms, Journal of Mental Health, 29:4, 473-482, DOI: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1714005

[34] Maurer, Mia & Daukantaitė, Daiva. (2015). Grit and Different Aspects of Well-Being: Direct and Indirect Relationships via Sense of Coherence and Authenticity. Journal of Happiness Studies. 10.1007/s10902-015-9688-7.

Stuck In All Or Nothing Mode?

Your mind isn’t broken; it’s just running on autopilot.

Take the free Emotion System Audit and learn what's driving your patterns - and what to do when you feel overwhelmed or out of control.